Is the Human Mind Massively Modular?

Good and bad faith debates around evolutionary psychology.

Modularity of mind is an ongoing debate both in and around evolutionary psychology (Barrett, Dunbar, & Lycett, 2002) with the central question being: does the human mind work as a general-purpose (domain-general) information processor, which can adapt flexibly to many situations, or does it contain many discrete and specialised (domain-specific) processors that have been shaped by selection pressures over evolutionary time to solve recurring human fitness problems, and which now constitute the architecture of the mind as specialised adaptive psychological mechanisms aka “modules”?

In this essay, I will look at the empirical evidence that supports the modularity hypothesis and latterly, will include a further comment about whether the module metaphor is a useful construct for organising research and explaining nervous system phenomena at various levels

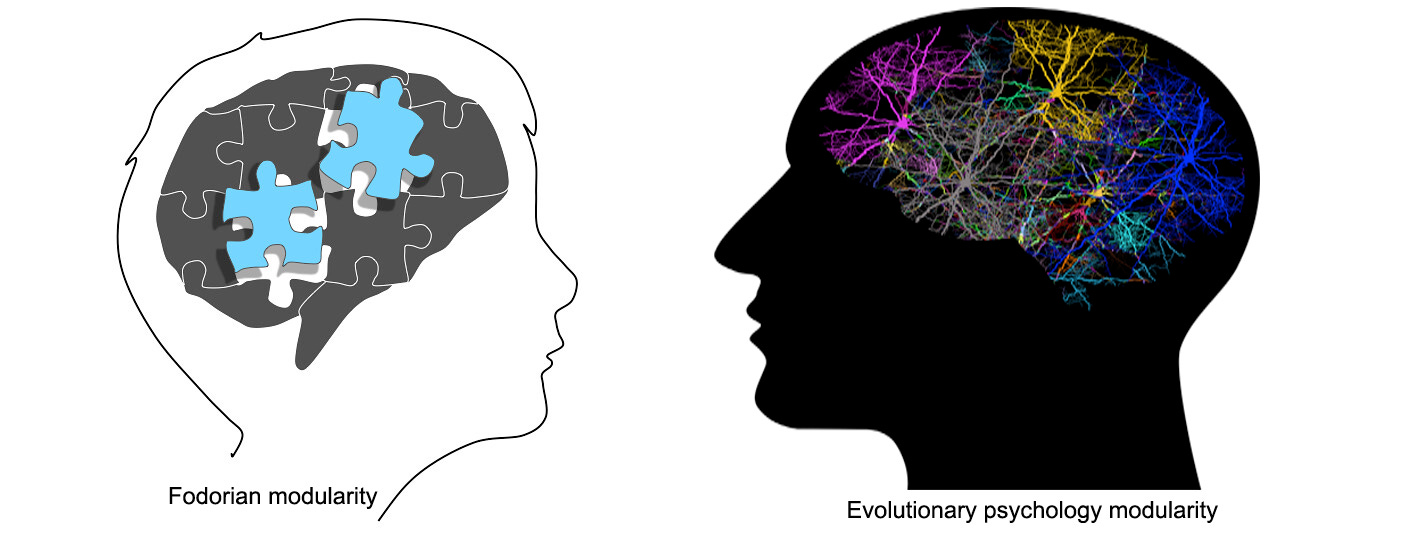

The concept of modularity was first introduced by Chomsky, who hypothesised a module for language. The concept was further expanded by philosopher/linguist Jerry Fodor (Fodor, 1983) to include perceptual processors.

At this time, cognitive psychology and neurology were dominated by an "interactionist" or general-purpose view of cognitive architecture which stressed a domain-general view of human perceptual processes. Fodor was the first to propose that the mind was made up of many specialised, domain-specific “modules” described as “special purpose modules” or “input systems” (Barrett et al., 2002) which were, inter alia, autonomous, encapsulated, problem-specific mechanisms functioning at a level below consciousness. Effectively, modules were “mindless agents” (Minsky, 1991) running an organisms essential system programmes in the background.

Anthropologist John Tooby and cognitive psychologist Leda Cosmides - the husband and wife the founders of evolutionary psychology - extended Fodor’s metaphor to include many more higher cognitive, intentional processes, such as mate preferences and cheater detection (Cosmides & Tooby, 1994). This is now what is known as the massive modularity hypothesis and differs from Fodor’s moderate modularity in that it proposes that the mind is almost entirely made up of such functional adaptations (Carruthers, 2008).

The discussion is further nested within the eternal nature/nurture philosophical debate, which asks if humans are born with minds as “blank slates” to be moulded by experience alone (Pinker, 2002) a paradigm that remains popular within much of the social sciences and humanities. The existence of domain-specific modules, and massive modularity particularly, is a major challenge to the blank slate view. Thus, as stated above, advocates of massive modularity defend the concept on two fronts, both within evolutionary psychology and without.

“All psychological theories...imply the existence of internal psychological mechanisms, but to what degree - massive or moderate, domain-general or domain-specific.” (Buss, 1995)

Evolutionary psychology merges cognitive psychology and evolutionary biology (Barkow, Cosmides, & Tooby, 1992) in the quest to map the human mind and nature (Cosmides & Tooby, 1994). The edges of that map are yet to be drawn and, contrary to many critics, evolutionary psychology does not impose any limits.

Briefly, cognitive psychology led to insights via the construction of information processors, whilst evolutionary biology added a functional perspective. These perspectives have helped evolutionary psychologists begin to “understand how the mind is possible, what kind of mind we have and why we have the mind we have” (Pinker, 2005). Evolutionary scientists and scholars who do not subscribe to the massive modularity hypotheses distinguish themselves from evolutionary psychologists by calling themselves, inter alia, human behavioural ecologists, evolutionary anthropologists and sociobiologists.

The empirical evidence in support of moderate, Fodorian modularity is strong. One of Fodor’s necessary conditions of a module is that it is autonomous and encapsulated, meaning there is no communication between one module and another. This encapsulation hypothesis has been tested in experiments with patients who have undergone split-brain surgery (LeDoux & Gazzaniga, 1981), a procedure to treat severe epilepsy where connections between the left and right hemispheres of the brain are severed. In these experiments, one side of the brain is set a simple task and the other side is asked to answer it, and, it has been discovered - cannot.

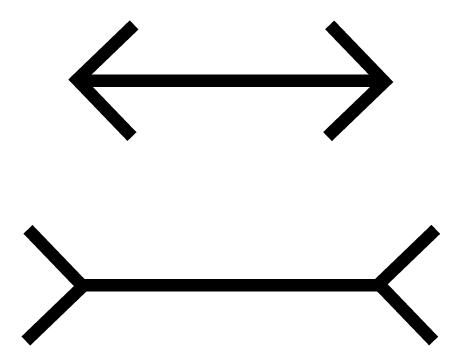

Similar results come from experiments with phantom limb patients (Ramachandran, Rogers-Ramachandran, & Cobb, 1995). These patients know and can see that their limb has been removed but a part of their brain continues to stubbornly feel pain in it. The list of empirical evidence continues from complicated experiments on patients with conditions such as “blindsight” and “alien hand syndrome” to simple optical illusions such as the (aptly named) Muller-Lyer illusion (below) where knowing the lines are the same length does not stop the mind from perceiving one as shorter or longer than the other (Kurzban, 2010).

The Muller -Lyer illusion (Franz Carl Müller-Lyer 1857 - 1919)

Some more ecologically rational, and slightly saucy, examples that will make you second guess yourself…

…of a lamp and a book.

Carruthers (Carruthers, 2008) identifies three main arguments supporting the massive modularity hypothesis. Firstly, Carruthers notes that modularity follows the pattern of all biological systems, from cells to extended phenotypes such as beehives, which are built hierarchically, subsystem by subsystem. Following the law of parsimony, there is no evolutionary logic to suggest the human mind is a special case that goes against this universal pattern. Secondly, he cites the shared developmental pathway between humans and other animals across evolutionary time. Animals have their own suite of specialised learning mechanisms for innate senses such as navigation, orientation, and memory, and once again, there is no logic (except divine) that would place humans as a special case in evolution. Thirdly, he cites the computational theory of mind, a theory Fodor supported, which demonstrates that complex computers cannot run on general-purpose programmes and the human mind is vastly more complex than any computer yet made by humans.

A domain-general processing system is “a system that lacks a priori knowledge about specific situations or problem domains ”(Barkow et al., 1992). Defenders of MM assert that domain generality is a sub-optimal system for an organism, as in a crisis, the organism must compute then select from all behavioural possibilities (e.g., smile, frown, recognise kin, eat, run, stay, point finger, scream) within microseconds. This problem of choosing amongst an almost infinite number of possibilities when only a few, and perhaps only one, is appropriate to save your life, has become a notorious problem for researchers of artificial intelligence known as the “frame problem” (Pinker, 2005). Evolutionary psychologists call this failure of processing a “combinatorial explosion” (Cosmides & Tooby, 1994) which paralyses any system that is truly domain-general.

Criticisms of an evolutionary psychology approach to human behaviour - which amounts to the application of ultimate evolutionary causation to proximate human psychology and behaviour; two distinct levels of analysis (Tinbergen, 2005) - have a long history that pre-dates evolutionary psychology itself.

Many critiques stem from 1975 and the publication of E.O. Wilson’s book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis (Wilson, 1975). Wilson’s book incorporated and synthesised uncontroversial, orthodox ideas of animal behaviour with functional, evolutionary biology. Problems arose however when, in the last short chapter, he also prosaically suggested humans were subject to the same universal laws as other organisms (Buss, 2019. p16). It was this latter development that many scholars who were epistemically attached to blank slate theories of the human mind - both scientifically and politically - objected to (Buss, 2019. p17).

In response to Wilson’s book, a group of academics created a watchdog committee (Sociobiology Study Group of Science for the People, 1976) specifically to critique Wilson’s last chapter (19 pages out of nearly 700), viewing humans as animals. Accusations of “extreme adaptationism” “biological determinism” and “optimal” design were levelled at Wilson (Gould & Lewontin, 1979) with the aim of discrediting the thesis. Unfortunately, it is not within the word limit of this essay to discuss the full exclamation and reply of this discourse. Suffice to say, each of these criticisms has been answered in full countless times. For a full review see (Segerstråle, 2001).

Nearly 50 years on, we find contemporary critics of evolutionary psychology - especially researchers in sex and gender (Gannon, 2002) who still follow the blank slate perspective of human nature - simply adopting these historical critiques, believing them to be relevant today. They are not (Campbell, 2002).

This is unfortunate as it continues to muddy the waters of debate between evolutionary psychologists, sociologists and feminists; debates which are often politically, rather than scientifically, motivated.

This, coupled with the ongoing lack of clarity about massive modularity, breeds distrust - perhaps on both sides but certainly on the side of evolutionary psychologists. It is important to note that evolutionary psychologists find good faith challenges against the massive modularity hypothesis legitimate and productive. (Kurzban & Haselton, 2006) The lack of empirical evidence to support the massive modularity hypothesis is often used by critics of evolutionary psychology to discredit the whole project. This is in spite of the fact that evolutionary psychology ranks in the top 10 of the replicability rankings of psychological journals (Schummack, 2022).

Empirical support for moderate modularity is strong, but that is not the case for massive modularity, such as Tooby and Cosmides cheater detection module, which has not yet been empirically observed. These scientific bottlenecks however are common and are a well-documented occurrence throughout the last 150 years or so of psychology's scientific history.

At the moment, the massive modularity hypothesis is more theory-driven, resting on Trivers' theory of reciprocal altruism (Trivers, 1971), than empirically driven. It is predicted to exist but has not yet been robustly empirically demonstrated. Until that occurs, it is little more than a thought experiment. Yet to dismiss it as a “just-so story” is also to dismiss much of science, social science and all feminist theory.

So to the question. Is the human mind massively modular? I find the hypothesis compelling, but also find it open to much confusion and misrepresentation due to the use of the “module” metaphor itself. If the metaphor were sufficient, there would be no need for further qualifiers, yet in every paper written on the subject, the term “module” is always followed with further adjectives, such as “systems”, “programmes”, “mechanisms”, “iPhone apps”, “swiss-army knife”; each one being a more efficient metaphor than the term “module” itself.

The term “module” evokes a singular piece of inorganic equipment to be added, or docked, into the brain like a jigsaw piece, representing Fodor’s encapsulation hypothesis well. In evolutionary psychology, however, the concept is far more evocative of an organic cascade.

Many areas may be encapsulated, as demonstrated empirically, but many may not. We simply do not know yet.

Conclusion

There are many criticisms of the massive modularity hypothesis, some good faith and some bad which is compounded by the lack of empirical evidence. I would suggest the term “module” is a bad fit for what evolutionary psychologists generally, and Tooby and Cosmides specifically, are theorising. Science depends on the use of accurate and precise terms, and as such, the vague term “module”, casts more shadow than light on the subject. Going back to Buss’ quote, the mind is undoubtedly modular, but at the present moment, we find ourselves hampered by the limitations of technology to know to what degree.

This was an MSc essay which was awarded a distinction (suitable for publication) .

Thanks to Gene Mesher for pointing out some typos and errors. As someone with a clinical diagnosis of ASD1 and pending a diagnosis of ADD/ADHD I know I’m not a great copy editor, especially of my own stuff.

References

Barkow, J. H., Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (1992). The adapted mind: Evolutionary psychology and the generation of culture Oxford University Press.

Barrett, L., Dunbar, R., & Lycett, J. (2002). Human evolutionary psychology (1st ed.) Palgrave.

Buss, D. M. (1995). Evolutionary psychology: A new paradigm for psychological science. Psychological Inquiry, 6(1), 1-30. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli0601_1

Campbell, A. (2002). A defence of evolutionary psychology: Reply to Gannon. Psychology, Evolution & Gender, 4(3), 265-281. doi:10.1080/14616661.2002.10383128

Carruthers, P. (2008). Précis of the architecture of the mind: Massive modularity and the flexibility of thought. Mind & Language, 23(3), 257-262. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0017.2008.00340.x

Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (1994). Origins of domain specificity: The evolution of functional organization. Mapping the Mind: Domain Specificity in Cognition and Culture, 85–116.

Fodor, J. A. (1983). The modularity of mind: An essay on faculty psychology. London; Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. Retrieved from https://go.exlibris.link/n8bp1Tbs

Gannon, L. (2002). A critique of evolutionary psychology. Psychology, Evolution & Gender, 4(2), 173-218. doi:10.1080/1461666031000063665

Kurzban, R., & Haselton, M. G. (2006). Making hay out of straw? real and imagined controversies in evolutionary psychology. In J. H. Barkow (Ed.), Missing the revolution: Darwinism for social scientists

Minsky, M. (1991). Society of mind. Artificial Intelligence, 48(3), 371-396. doi:10.1016/0004-3702(91)90036-J

Pinker, S. (2002). The blank slate: The modern denial of human nature. London: Allen Lane. Retrieved from https://go.exlibris.link/TsPPWD0P

Pinker, S. (2005). So how does the mind work? Mind & Language, 20(1), 1-24. doi:10.1111/j.0268-1064.2005.00274.x

Ramachandran, V. S., Rogers-Ramachandran, D., & Cobb, S. (1995). Touching the phantom limb. Nature (London), 377(6549), 489-490. doi:10.1038/377489a0

Schummack, U. (2022). 2022 replicability rankings of psychology journals. Retrieved from https://replicationindex.com/2022/01/26/rr21/

Sociobiology Study Group of Science for the People. (1976). Dialogue. the critique: Sociobiology: Another biological determinism. Bioscience, 26(3), 182-186. doi:10.2307/1297246

Trivers, R. L. (1971). The evolution of reciprocal altruism. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 46(1), 35-57. doi:10.1086/406755

Wilson, E. O. (1975). Sociobiology: The new synthesis. London; Cambridge [Mass.]: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. Retrieved from https://go.exlibris.link/T2ht0JpD